Here's the wicked problem of game balance: you definitely do not know how to solve your game, but you must somehow balance it.

By solving, I mean you cannot determine how to play your game optimally. In this article on solvability, I covered what playing optimally actually means. For games with a pure solution, it means a set of instructions that's the best way to play. Knowing those instructions means there are no more decisions or strategy in your game. For games with a mixed solution, there still could be strategy, but you'd have a far much more interesting game if no one knew how to play optimally.

If you can solve your game, your players can definitely solve it. If you can’t solve your game, your players might still solve it. In any case, we know you can’t solve it because that means you didn't make an interesting enough game in the first place.

How in the world can you balance something when it’s impossible to know the best ways of playing it? If you aren’t worried about this, then you don’t understand how distressing the problem is. The techniques I discussed in the previous three articles will help, but they remind me of what art director Larry Ahern said when he was preparing to draw all the backgrounds in The Curse of Monkey Island. He said that by following the rules of composition from classical painting, he believed he could get results that were "not terrible." But, he said, going from not terrible to great was something he hoped he had within him, and that it's not exactly possible to get there by following someone else's cookbook of rules.

Picking The Top Players

Let’s back up to an easier problem. Imagine I gave you a room full of players of a certain game and I asked you to determine who the best player is, and who is second best. How would you do it? Answer: you would have them all play each other.

What if I don’t let anyone play the game, though? I’ll let you interview the players or have them submit written answers to your questions about how they will play the game and what they know about the game. Can you determine the best players from this method? I bet you will do only slightly better than monkeys throwing darts to determine the answer. In all my experience running and competing in tournaments, I can say with some authority that there is little correlation between ability to win and ability to explain yourself.

Why are the best players not necessarily able to reveal themselves as best through interviews or speaking? I claim there are two reasons:

1) Spoken and written answers have extremely narrow bandwidth.

2) It’s impossible to access many of our own skills with conscious thought.

Both of these ideas have to do with the concept of the mental iceberg.

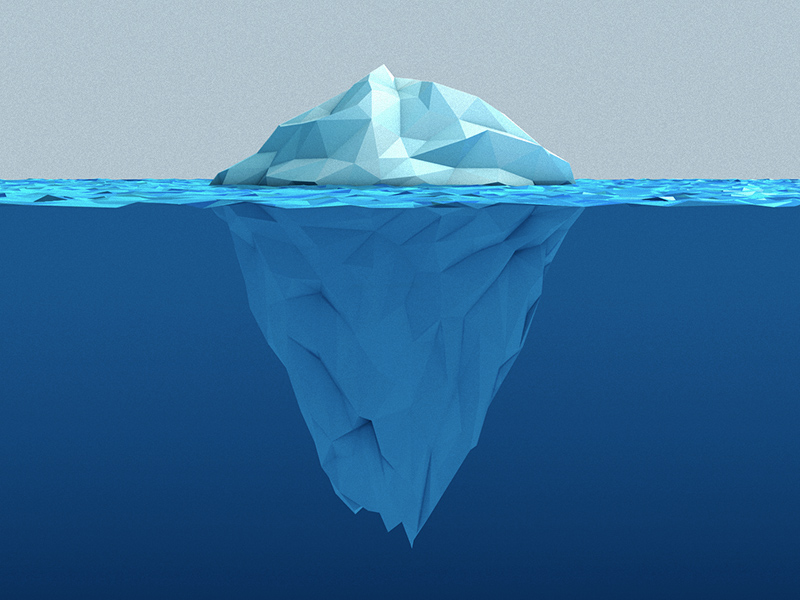

The Mental Iceberg

Imagine an iceberg that represents your total knowledge, skill, and ability at something, for example in playing a certain competitive game. The small part of the iceberg above the waterline is what you have direct conscious access to; it’s what you can explain. The gigantic underbelly of the iceberg is the part you do not have direct access to, and yet it accounts for far more of your overall skill than the exposed tip. When we interview players or ask them for written answers about how they might play, we are only accessing the tip. If one player’s iceberg has a larger tip (they tell a better story about how they will win), it’s entirely possible that their hidden below-water iceberg is much smaller than another player’s, and that’s really what matters.

The above-water part of the iceberg represents what you can explain or consciously understand. The huge underside represents your vast unconscious.

Narrow bandwidth

The amount of information you can convey in a written or spoken answer is actually very small compared the storehouse of knowledge and decisions rules you have stored in your head. Also, spoken and written language encourage linear thinking, while your actual decision-making might be a more complex weighting of many different interconnected factors. In a written answer, a player might say “move A beats move B, so I will concentrate on using move A in this match.” But really it might depend on many factors: the timing of move A, the distancing, the relative hit points of the characters, the mental state of the opponent, and so on. Players cannot communicate these nuances in an explanation the way they can enact them during actual gameplay.

No Direct Access to Parts of Our Own Minds

You don't know most of what's going on in your own brain or body. This concept might be hard to swallow at first, but it should be incredibly obvious if you think about it for a moment. You are not conscious of how your digestive system works. You do not have direct access to how your cells make and break the bonds of ATP and ADP to give your body energy. When you see a frisbee travel across the sky, you are not aware that your eye moves in a particular pattern of jerky movement called saccades that are common in all humans (you believe that you smoothly follow the moving object).

One study estimates that the human brain takes in about 11,000,000 pieces of information per second through the five senses, yet the most liberal estimates say that we can fit at most 40 pieces of information in conscious memory. There is A LOT going on behind the scenes, and we do not have conscious access to it, even though we are still able to make decisions that leverage all that information. (Wilson, p.24.)

Blindsight

The medical condition of blindsight is a particularly telling example. Blindsight is blindness that results from having damage to a certain part of your visual cortex. There are actually two different neural pathways for vision, and people with blindsight have only one of these pathways blocked. The result is that they are blind, meaning specifically that they don’t consciously experience seeing. Even though they claim to see black, they can still make decisions based on eyesight. In one experiment with a blindsight subject named DB, experimenters showed him a circle with either vertical or horizontal black and white stripes. Even though he can’t see so he has no idea whehter the stripes are horizontal or vertical, and sometimes become agitated when asked to guess, his “guesses” were correct between 90 and 95 percent of the time. In other words, people with blindsight can perceive the world more accurately than their conscious minds can explain. (Blackthorne, p.263.)

Instant Decisions

Another clue to this concept lies in decisions that we make extremely quickly. Consciousness does not coalesce instantly; it takes somewhere between 0.3 to 0.5 seconds to form. I know that that sentence is highly controversial amongst brain researchers, but I think it’s generally safe to say in times shorter than that, we have not yet formed enough of an awareness about what’s happening to be conscious of it. And yet, experiments show that we make decisions based on outside stimulus faster than this. For example, when people are asked to grab wooden rods as they light up a certain color, and the experimenter cleverly lights up one rod, then as you are reaching for it, darkens that rod and lights up a different one, he can measure when your hand made the course correction to go for the newly-lit rod. The course correction occurs almost immediately, much faster than 0.3 seconds, and yet the subjects believe they course correct only at the last moment, after 0.5 seconds. In fact, they don't even consciously percieve that the lights on the rods changed until after they made the course correction! They are making decisions before they are conscious of what is going on.

Tennis is more real-world example of this. Tennis pros can serve the ball at 130mph, and the distance between baselines is 78 feet. That means it takes 0.41 seconds for the ball to reach the opponent. New York Times writer David Foster Wallace said:

The upshot is that pro tennis involves intervals of time too brief for deliberate action. Temporally, we’re more in the operative range of reflexes, purely physical reactions that bypass conscious thought. And yet an effective return of serve depends on a large set of decisions and physical adjustments that are a whole lot more involved and intentional than blinking, jumping when startled, etc.

(New York Times.)

Tennis pro Roger Federer has explained in interviews that he doesn’t like to be called a genius at the game, because he doesn’t think during the incredible moments when he returns balls few other players can. He acts before he is conscious of the situation by leveraging his unconscious skills.

Heuristics We Use But Can't Explain

Baseball gives us another important example. How do fielders catch fly balls? It seems like a very complex math problem with variables for speed, trajectory, gravity, friction from air resistance, wind influence, etc. Should fielders run as quickly as they can to the general location where the ball will land, then make adjustments as they solve these equations somehow?

No. The best way to catch a fly ball is to use the gaze heuristic, as described in the book Gut Instincts. The method is to look at the ball, start running, and adjust your running speed so that the angle of your gaze remains constant. You will then reach the ball just as it lands, and you’ll be in the right place. Experimenters found that the best professional baseball players use this method (and so do dogs), but that most of the players don’t know that they use it, and are unable to explain any method they use to catch fly balls. (Gigerenzer, p.10.)

This example shows that it’s very possible for the correct answer to be hidden in your mental iceberg’s underbelly, but it’s not necessarily a representative example. I chose it on purpose because the underlying decision process can be simply described, which allows me to describe it to you. But what if they underlying decision process relies on a complex weighting of variables that isn’t easy to describe? This is another clue that explanations of how to solve complex problems are just tips of the iceberg, and not necessarily accurate.

Before we get back to solving our mind-bending task of balancing a game that we can’t possibly know how to play optimally, I’d like us to look at two cases outside of games where experts solved very difficult problems. The different methods they used are applicable our problem, and to solving any other highly complex problem.

The Case of the Greek Statue

From an example in the book Blink, the Getty Museum of California was considering purchasing a 2,600-year-old Greek statue for almost $10 million. To determine if it was a fake, the museum had its lawyers investigate the paper trail of the statue’s ownership and whereabouts over the last several decades and had a geologist named Margolis

...analyze the material composition of the statue. The geologist extracted a 1cm by 2cm sample from the statue analyzed it using an electron microscope, electron microprobe, mass spectrometry, X-ray diffraction, and X-ray fluorescence. The statue was made of dolomite marble from the island of Thasos, Margolis concluded, and the surface of the statue was covered by a thin layer of calcite -- which was significant, Margolis told the Getty, because dolomite can turn into calcite only over the course of hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

After 14 months of analysis by the lawyers and scientists, the Getty was ready to buy the statue. And then the trouble started. When the Getty was nearing the unveiling of the statue, a few art experts saw it and each of them had an immediate reaction that something was wrong. They didn’t know what, but they thought it was a fake.

One of those experts was Thomas Hoving, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. When Hoving saw the statue, the first word that popped into his head was “fresh,” which he thought was an odd word to describe a statue that’s thousands of years old.

Thomas Hoving

The Getty was worried, so they shipped the statue to Athens where they invited art experts to a symposium to look at the statue. Most of them said it was fake, too. “It’s the fingernails” or “it’s the hands” or “statues don’t come out of the ground looking quite like that,” people said. They didn’t know just why, but they knew. Then the Getty’s lawyers discovered that some of the statue’s ownership documents had been faked. The geologist (who was so proud of his examination that he wrote an article about it in Scientific American) discovered that it was possible to convert dolomite to calcite in just a few months using potato mold.

How did Thomas Hoving know something instantly that the lawyers and scientists could not discover after 14 months of investigation? He knew because he had an enormous mental iceberg of knowledge and expertise in this exact area. He dug up statues himself in Sicily. He also said:

In my second year working at the Met, I had the good luck of having this European curator come over and go through virtually everything with me. We spent evening after evening taking things out of cases and putting them on the table. We were down in the storerooms. There were thousands of things. I mean, we were there every night until ten o’clock, and it wasn’t just a routine glance. It was really poring and poring and poring over things.

The lawyers and scientists had a large “iceberg tip” in this case. They had lots of explanations why the statues were real. But if there’s anyone in the world who has a tiny iceberg underbelly when it comes to knowledge about Greek statues, it’s laywers and scientists. Hoving’s iceberg tip was small (he just had a feeling), yet his iceberg underside was enormous. (Gladwell, pgs.3-11,184.)

Can you imagine trying to detect fake statues by asking Hoving to give you a theory of fake statue detection? What if his theory left out lots of things he unknowingly uses to solve the problem? What if his theory is actually wrong, and doesn’t reflect his methods at all (because he doesn’t know them himself)? That’s the inherent problem with requiring that any expert synthesize a theory of his own expertise.

The way to solve a complex problem is to develop an enormous iceberg underside. Is that just saying that you need “experience,” though? Experience is kind of a dirty word to me. George Bush has “experience” as a president and with foreign affairs. Do you want him running the country (or anything else)? Meanwhile Lincoln had hardly any experience. Experience is only as good as the person who has it, and even besides that, we usually use completely the wrong scale to measure experience.

If you have the experience of “shipping 10 games,” for example, that’s great but it doesn’t have anything to do with the particular type of experience--the particular iceberg of knowledge--that is involved with balancing a complex asymmetric game. Before we try to develop this iceberg, let’s look at one more example.

The Case of the Space Shuttle Disaster

Imagine that your problem is that you must determine how and why the Space Shuttle Challenger crashed. You are on the investigative committee, looking for this answer. What is the best way to solve this problem? Is it to be an extreme expert in aerospace engineering? Is it to be an expert at investigating disasters? The answer is to first live the life of Richard Feynman, then solve the problem.

I think Feynman is one of the most brilliant people who ever lived, and he demonstrated his ability to solve complex problems in many fields outside of his own field of physics. Feynman was not an engineer, but the shuttle problem required an engineering analysis. He was a fish out of water on the investigative committee, and had no experience doing anything like that. What he did have experience doing was analyzing problems in general. Taking in vast amounts of information, organizing it in his head, figuring out what mattered and what didn’t.

Richard Feynman

Feynman took nothing at face value, ignored the rules of the committee, questioned everyone he could, ignored authority figures and the politics of the investigation, and instead focused getting real information. His very first interview was a marathon session with the engineers who designed the shuttle’s rockets. They had the iceberg of knowledge he needed and he knew how to get at least a piece of it out of their heads and into his own. By ignoring illusions like who had important titles or who supposedly knew anything and instead focusing on who actually had the relevant icebergs of knoweldge, Feynman—and no one else on the commission—discovered that the real problem with the shuttle was lack of resilience of the rubber O-rings during cold weather. (Feynman, pgs.113-153.)

If you are going to solve a complex problem, the two best ways are to be like Hoving or to be like Feynman. When I worked on Street Fighter, I was like Hoving. I have a mountain of knowledge about that particular game, so my expert opinion, even if it expresses itself as just a feeling, is worth a lot. On other games I worked on such as Kongai and Yomi, I was more like Feynman. I know how to solve balance problems in general, but there are playtesters who have bigger icebergs of knowledge about how to play the game at an expert level than I do, so I question them, watch them, and rely on them.

Developing the Iceberg

How do you actually get the iceberg of knowledge in the realm of balancing competitive games? Ideally, you want the Feynman-type of ability that can be applied to many types of problems, not just a very narrow domain of one game.

The problem with developing this type of knowledge is time. If we are instead trying to become expert players (rather than expert game balancers), we have access to a very fast feedback loop. Play the game against people better than us, see what worked and didn’t, adjust, play again. A game of Street Fighter takes only a couple minutes, and even an RTS game takes less than 1 hour. But creating a game and seeing how its balance turns out takes years. It’s a very slow feedback loop, and extremely few people get to even participate in it directly.

I think that there is a way to gain the necessary knowledge though. Here are the games I studied:

1) Street Fighter. I'm knowledgeable about more than 20 versions of this game.

2) Virtua Fighter. It says version 5 on the box of the latest one, but really, there have been at least 15 versions of this game if you look closely.

3) Guilty Gear. I know about 8 versions of this game.

4) Magic: The Gathering. This game has changed (with new sets of cards) about 3 times per year for over 10 years. I followed it for several years.

5) World of Warcraft. I played that game for two years before it was released and I couldn’t even guess the number of mini-releases over that time. Maybe 50 or 100.

That is A LOT of data about how changes to a game’s balance out. You can study what the exact changes are from one version of a game to the next, then learn how those changes actually affected the game’s balance and how they players perceived the changes. I actually count those as two separate things, and on Street Fighter I had two separate main advisors: one who knew the most about how a change would affect the game system itself, and another who knew the most about how players would perceive changes.

You have to put in real, effortful study on following games like the ones I listed above, though. Just being along for the ride doesn’t necessarily get you much. Also, experience working at a game company is almost a detriment here, because game companies I’ve worked at don’t spend any time looking at things like “exactly why did Virtua Fighter change this move’s recovery to 8 frames?” Instead, the focus is on actually implementing and shipping games.

I also think that you can’t really fake this. There is no way I could have accumulated the knowledge that I have if my motivation was to be better at my career. My motivation is that I am actually interested in things like this. Thomas Hoving was actually interested in art history. You have to live an authentic life in your chosen area of interest to develop true, deep knowledge of it.

Garcia vs. Sirlin (Analysis vs. Intuition)

In Street Fighter, there is no possible way to create a "balancing algorithm" that will tell you if Chun Li's walking speed should be faster. How good is faster walking speed compared to damage on her fierce punch, compared to priority of her ducking medium kick, etc? You could do a year of math on that and still be more wrong about it than my guess in two seconds.

I was very aware of this when I designed Kongai, and I tried to make it as difficult as possible to compare the relative value of moves because of their varied effects. I wanted valuation (the ability of players to intuitiely know the relative value of moves in specific situations) and yomi (the ability of players to know the mind of the opponent) to be the two main skills in the game. And then I encountered garcia1000, a Kongai player who came from the poker community. While my goal as a designer is to facilitate valuation and yomi, garcia's goal as a player is to play optimally without needing to make any judgment calls on those things at all. He want's to compute the odds and solve the game. You could say that he's my worst nightmare, but he is work is also fascinating.

Garcia started by creating several endgame problems in Kongai. He chose very specific situations, Character A vs. Character B, all other characters are dead, life totals a certain amount, fighting range set to far, item cards given, etc. He would give very specific situations (which were much simpler because there are fewer chioces during the endgame), and then invite other testers to work out the solution for optimal play. Each specific situation took dozens of pages of forum posts to settle. They would also show amusing things such as optimal play giving a 3% edge over the more obvious plays, in one case. It was also amusing that the math reequired to solve these endgame situations was far more complicated than the math I used to set all the tuning variables. (Because I mostly used intution....)

What you have to keep in perspective though, is how limited these endgame solutions are. You could know the solution to dozens of them and you wouldn't have solved even 0.00001% of the game. The number of possible game states is very large indeed, and each of these endgame problems that took dozens of pages of posts to figure out solved only ONE gamestate. If I had used rigorous math to solve Kongai during development, I could have been working on it for 100 years.

Trusting Intuition

If you have this iceberg of knowledge, or if you’re like Feynman who can rely on the icebergs of others, you should still know two things about maximizing the value of intuitions. Intuition by experts is better at solving complex problems than analysis, but:

1) The intuitive expert will be less sure of their answers, while incompetent people will be very sure of their (wrong) answers.

2) Having to explain yourself diminishes your ability to draw on your intuition in the first place.

This is too large of a topic to go into depth on here, so I’ll give only a short summary. There’s a wonderful study on incompetence that shows that people who are incompetent at a task (logic, humor, grammar, etc.) grossly overestimate their own ability at the task and are unable to detect expert performance in other people who actually are skilled at the task. The reason is that the very knowledge they lack to do the task is the same knowledge they need to evaluate themselves and others.

The result is that you will definitely have to deal with the loud complaints of incompetent people who are quite sure of themselves, and who might even have a well-developed tip-of-the-iceberg of reasoning, but no underside to their iceberg at all. I suggest somehow gaining enough authority that your vague feeling on a balance issue is able to trump their loud complaints. You might even try explaining why that is best for the game.

Several studies show that explaining yourself wrecks your intuition. If you see a person’s face, then must identify that person later in a lineup, you will do much better if you do NOT have to explain the face in detail beforehand. Your explanation is imperfect because the bandwidth of words is so narrow, yet your knowledge of the face is nuanced. The story you create about the face overwrites your actual knowledge and makes you perform worse in the lineup test. Other studies show that requring an explanation of thought process makes test subjects less able to come up with creative solutions for problems.

While balancing Street Fighter, I had the luxury of not having to really explain myself to anyone, and that was a great advantage. Note that I happily explained everything after the fact, but I’m talking about in the heat of development. If I wanted to try a balance idea, and I wasn’t exactly sure why I wanted to try it, I could. I did not need to convene a meeting and lay out a logical plan that people voted on. I could just do it, and test it.

There was a brief period of disaster where a new producer tried to track every single task I planned to do in the balancing process. I was reluctant to submit any list of future changes because every day, the landscape changed. Tomorrow I might learn how to implement something that I thought before was impossible to implement. The next day I might learn that a recent change removed the need for some other future change, based on playtest results. Every day, the thing I worked on was whatever thing I felt was most important that day.

The agility that method allowed was amazing, and it's the only way I can imagine doing things. I think it’s pointless to track my work in the way that producer wanted to because doing so gives the overall project no advantage, while it damages my ability to draw on my intuition. Game balance has not been on the critical path of development on any game I’ve ever worked on, meaning there’s always some other thing that pushes out the ship date. In balancing, you keep doing it and doing it until someone says you have to ship.

My advice to not explain yourself and to have the authority to ignore incompetent complainers unfortunately sounds like a recipe for creating an ego-centric dictatorship that ruins a project. Yet the best way to leverage intuition is to gain that kind of power on a project, and then not use it much. You want your subordinates to do their best jobs without having to explain every little thing to you either, after all. (Alternative: you could work at Valve where no one is anyone else's boss. Yeah really.)

Conclusion

Balancing a game when we know we can’t know how to play that game optimally is a deeply troubling problem. Logical analysis often fails at this type of complex problem because it doesn’t take into account all the nuances that our unconscious minds and intuitions can. To solve this balance problem, or any similar problem, we should build up a vast mental iceberg of knowledge and experience in the field. I don’t mean fake experience like working at a game company or getting your name listed in credits though, I mean real experience which only comes from effortful study. Use your own iceberg of knowledge in the form of intuition and seek out others with vast icebergs of knowledge and rely on their advice. Finally, somehow acquire enough power on a project that you don’t let your valid feelings about what to do get trumped by loud disagreement from incompetents and don’t let your intuition be destroyed by anyone who demands constant explanations of your every decision.